Ever wonder how some of your favorite artists created their colors on canvas? It’s only been relatively recently in western art history (that is, around the 19th century) that paints began being mass-produced. Just how did western painters make or acquire their paints prior to then?

The history of color and paints is a long, fascinating journey, and it would probably take us far over 10 blog posts to even scratch the surface of pigments created throughout history, without even delving into color theory. Today, however, we’re going to take a brief look at a few ways three of the most striking color paints used in western art history were created

Cochineal-Derived Red

Portrait of a Cardinal by ADP featured artist Raphael, 1510. Image c/o Wikimedia.

While Europeans were busy grinding up clay and minerals to produce their reds, Latin American communities had for centuries been creating a much deeper red from the smashed remains of the cochineal bug. When crushed, this catcus-dwelling insect becomes a vibrant red. After they were done conquering and infecting local populations, Europeans went nuts for that cochineal red, as most European red paint couldn’t hold a candle to this bold “new” red.

They began shipping the cochineal back across the Atlantic in ridiculously large numbers, mainly because it takes thousands of insects to produce a small amount of dye. As the commodity became the third biggest import from the new world, Spanish cochineal ships were even targeted by English privateers. (Can we please have a Pirates of the Caribbean remake with this included?)

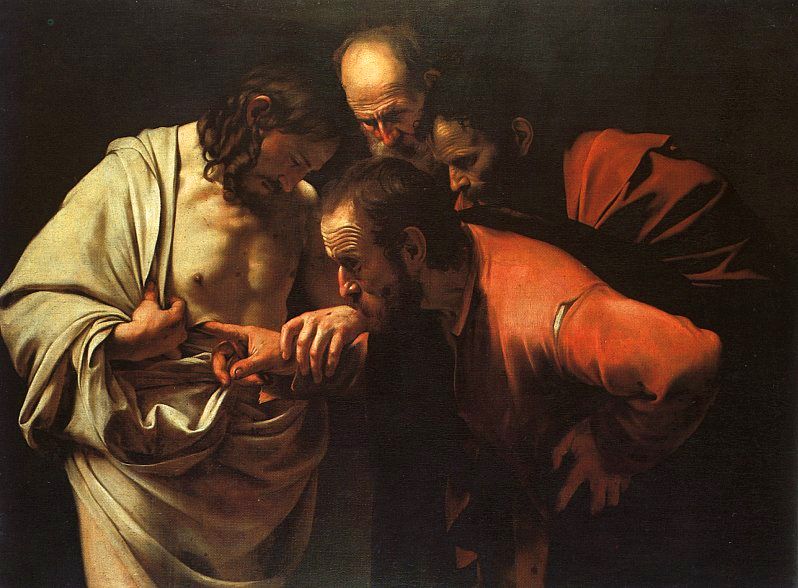

Thus, cochineal-derived reds were wildly expensive in the 16th and 17th centuries, and were used to create bold red paints. Though synthetic reds have largely usurped cochineal’s use in paints today, it’s found other uses in dye used in food and lipsticks. But hey, at least it’s nontoxic.

Ultramarine Blue

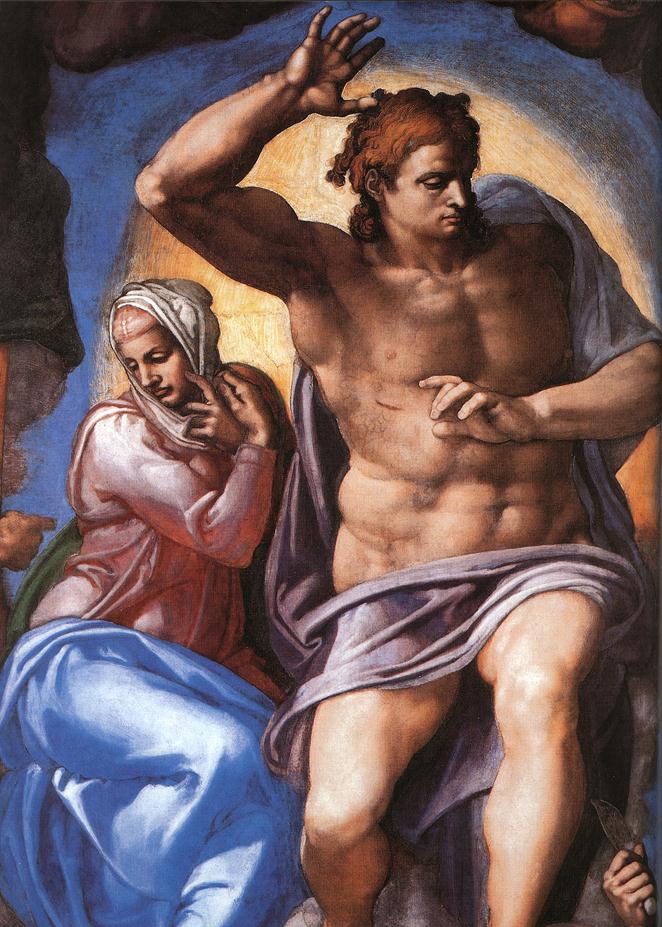

Lapis lazuli, a semiprecious stone mined from mountains in Afghanistan, is by far western art history’s most prized blue. Its popularity dates back to ancient times, as there’s evidence that the ancient Egyptians couldn’t get enough of it either. Used to create deep blue paint, lapis lazuli had to travel quite far to reach Europe, making it the most expensive color for the majority of western art history. Reflecting its origins, the color created from lapis lazuli is called ultramarine blue, meaning “blue from across the sea.”

This blue was typically used relatively sparingly in art history–that is, unless the person commissioning the artwork in question was rich, in which case they’d show off their wealth by telling the artist to run wild with the blue.

Royal/Tyrian Purple

Purple has long been associated with royalty, and for good reason–purple is historically one of the most expensive paint colors to produce. Since ancient times, purple dye was made from the excretions of the Mediterranean-dwelling Murex sea snail, which produces a deep purple ink-like secretion when antagonized. Christened Tyrian purple (after its major harvesters in Tyre in modern-day Lebanon), extracting the ink to transform into paints and dyes was labor-intensive and costly, as it also took a great deal of snails to create a small amount of paint. For a time, the Murex snail was even driven to extinction.

This is probably why we don’t see quite as much purple throughout earlier western art history. However, with the invention of synthetic paints, purple became more accessible for all–especially the Impressionists.

Though most artists today choose affordable synthetic pigments, there’s still a demand for these traditional colors, especially in the field of art restoration. There’s even a shop in Florence called Zecchi that still creates and sells Blu Oltremare paint derived from lapis lazuli, as they have for centuries. And after Artsy ran an article about them earlier this year, we’re sure Zecchi will keep creating paint the traditional way for years to come, as restorers (and perhaps more artists themselves) try to match the vibrancy of these timeless hues.

Check out more on red from: Artsy, Medium, The BBC, Visual-arts-cork.com, and The Art History Babes podcast.

Check out more on blue from: Artsy, Dunn Edwards, The New York Times, and The Art History Babes podcast.

Check out more on purple from Charles Parsons, The BBC, Artsy, and The Art History Babes podcast.

What do we do here at the Art Docent Program? Discover more about us and our curriculum here!

Want more fun art articles? Check out our blog archives for more!

Don’t forget to follow us on Facebook for updates and more posts!