If you read last week’s blog post, you’ll know that this week, we promised to give you an updated, full-length version of the story of Han van Meegeren, the famous Dutch forger whose imbeccable forgeries fooled art experts and Nazi officials alike. (If you didn’t, you can still catch last week’s post by clicking here.) And so, without further ado, here–filled with as many plot twists as an Oscar-winning film–is the story of Han van Meegeren.

Born in the Netherlands in 1889, van Meegeren was a trained artist, according to Wikipedia. Though his original paintings received some attention in Germany, he was for the most part ignored, if not dismissed as mediocre, by critics in his home country. And he might have remained in relative obscurity if not for Hermann Goering (Göring).

Goering, one of the Nazi party’s chief military leaders, was also one of the regime’s most notorious art acquirers. For anyone who hasn’t seen Monuments Men, top Nazi officials were huge art lovers (so much so that Hitler wanted to create his own art museum), and thus took it upon themselves to take whatever art suited them in the areas they took over.

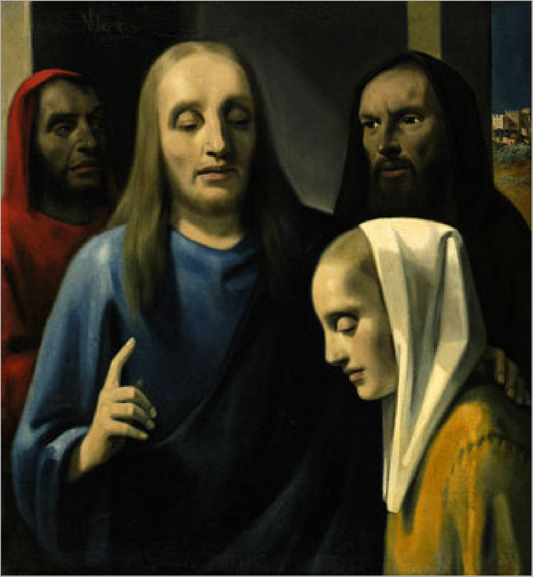

According to the Boijmans Museum (who have a spectacular video on this story that you can watch below), during World War II and in the years immediately preceding it, seven “undiscovered” Vermeers turn up. Why is this such a big deal? Jan Vermeer (featured in our curriculum here at the Art Docent Program) painted less than 50 works throughout his career and remains one of the most mysterious figures in the history of art. Yet all of these “newly-discovered” works were praised by Europe’s leading art critics as “missing links” (most were religious in nature, whereas true Vermeers are mainly genre scenes). With that in mind, the paintings command huge price tags, equivalent to millions today. Some are acquired by museums (including Amsterdam’s prestigious Rijksmuseum), and some are purchased by private collectors. And one, Christ and the Adulteress, is acquired by Hermann Goering himself.

After the war’s end, Allied officials tracked down people who collaborated to help the Nazis “acquire” (aka forcibly take) art. Following the trail of Christ and the Adulteress, Allied officials arrested Han van Meegeren in 1945 for collaboration with Nazi officials. Rather than face a long prison sentence, van Meegeren came clean and admitted to forging the painting, in addition to the other seven “recently-discovered” works and several works thought to be by Pieter de Hooch, among others.

But how? van Meegeren explained during his trial two years later. After years of meticulously studying and reproducing the respective techniques of Vermeet, de Hooch, and artist Frans Hals, van Meegeren also perfected a technique to make the paintings appear older than they actually were. After buying original, cheap 17th-century canvases (not sure where he found those, but still), van Meegeren would scrape off the top layer and paint on the cracked base layer, using a mixture of Bakelite (an early plastic [a “thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin,” according to Wikipedia]) and pigment. van Meegeren would then put his paintings in the oven, as this mixture would harden and crack when exposed to heat in exactly the way an older painting would simply due to age. After removing them from heat, van Meegeren would roll the canvases to bring out the cracks and then pour ink in the cracks to accentuate them.

To prove his story to anyone was still unconvinced, van Meegeren painted a stunning reproduction of one of his forged works during the trial, which removed all doubt as to his abilities as a forger.

What’s most interesting, perhaps, about the story of Han van Meegeren is the stature which he acquired between the period of his arrest and his trial (a two-year period) that still persists. On the one hand, he’s a forger–which is a crime against the art world. And yet his meticulous work managed to fool not only Hermann Goering, one of the Third Reich’s most-hated officials, but Europe’s leading art critics, who were viewed as elitist and snobby by the public and by most artists–which ended up making van Meegeren a national hero of sorts.

So, what do you think? Is Han van Meegeren a hero? Why or why not? Let us know what you think of all this in the comments below!

Want more on van Meegeren’s story? Check out Essential Vermeer for more, or watch this video from the Boijmans Museum.

What do we do at the Art Docent Program? Find out more here and follow us on Facebook!

Want more fun art stories? Check out our blog!