When looking at Christian western art, it’s can sometimes be difficult to discern just who is who. Identifying common figures and saints can be tricky, even if you have with a religious background. Which is why we’ve put together this little cheat sheet of saints and their attributes (aka items figures are pictured holding or shown in the scene nearby meant to help you identify the saint in question).

Just how did these attributes become associated with their respective saint? You can thank a little book called The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine from about 1260 for these relatively easily-recognized visual cues, as it goes into detail about the lives of the saints and was an important resource for many western artists. Though not factually accurate by modern standards of historical accuracy, it acted as an entertaining source that impacted visual depictions of saints for years.

Though our list here is by no means comprehensive, we’ve included saints and Christian figures who tend to pop up the most in religious art and have a relatively simple means of identification. Part I contains some of the most common saints that often turn up in paintings with Jesus, as they’re recorded as living during or shortly after his life span. For continuity’s sake, we’ll be referring to most of these figures with a St. before their names (and because they have been canonized by the Roman Catholic Church). And now, without further ado, we present Part I of our Saints & Attributes Cheat Sheet.

1. If she’s wearing blue (and/or depicted with someone who’s probably Jesus), it’s most likely the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ.

This one seems like a bit of a no-brainer, but depictions of Mary in western art history get more interesting the more you look at them. Traditionally, in Europe blue pigment and paint was one of the more difficult and costly shades to attain. According to Artsy, Byzantine artists first began using blue stones for Mary’s garments in mosaics dating from the Middle Ages. Early Renaissance artists like Giotto (featured in our curriculum) and Cimabue continued the tradition. Using such an elevated hue asserted Mary’s importance for viewers, and seems like a fitting choice for “the Queen of heaven.” Sometimes her blue garments also include a white section or shawl representative of her purity. And if she’s holding a baby, it’s Jesus 99.99% of the time.

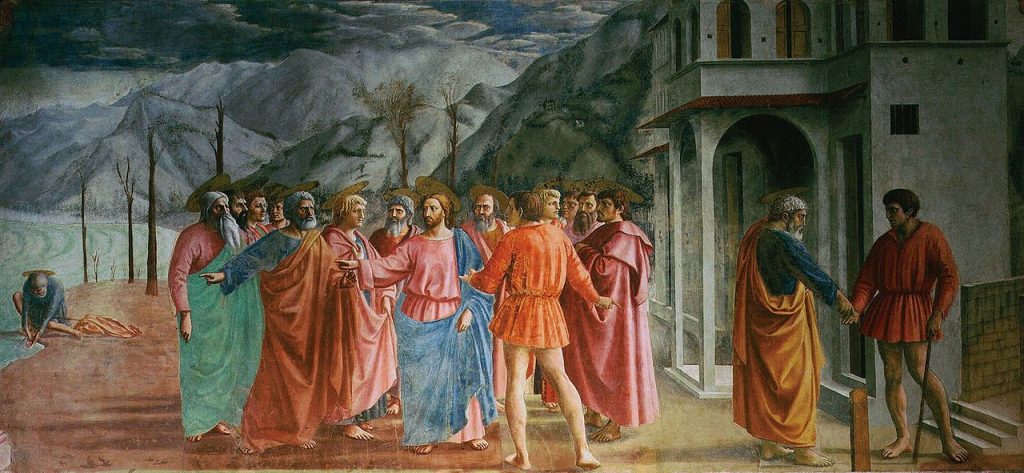

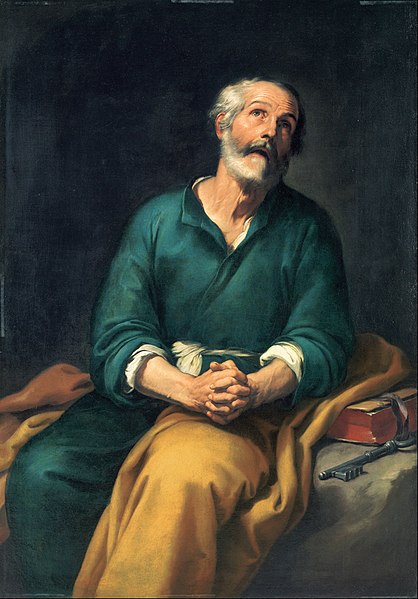

2. If he’s wearing gold and blue and/or holding keys, it’s most likely St. Peter, one of Jesus’ twelve disciples.

Gold and blue became associated with Peter at some point, though we’re not really sure why. The keys he sometimes is shown holding, though, make more sense: in Christian tradition, Jesus gave Peter the figurative “keys to the kingdom” when he instructed him to “feed my sheep.” Peter is thus recognized as the first pope in the Roman Catholic tradition. He may also be depicted with an upside-down cross, hinting at his manner of death: according to tradition, Peter didn’t consider himself worthy enough to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus, and thus insisted that his executioners crucify him upside-down.

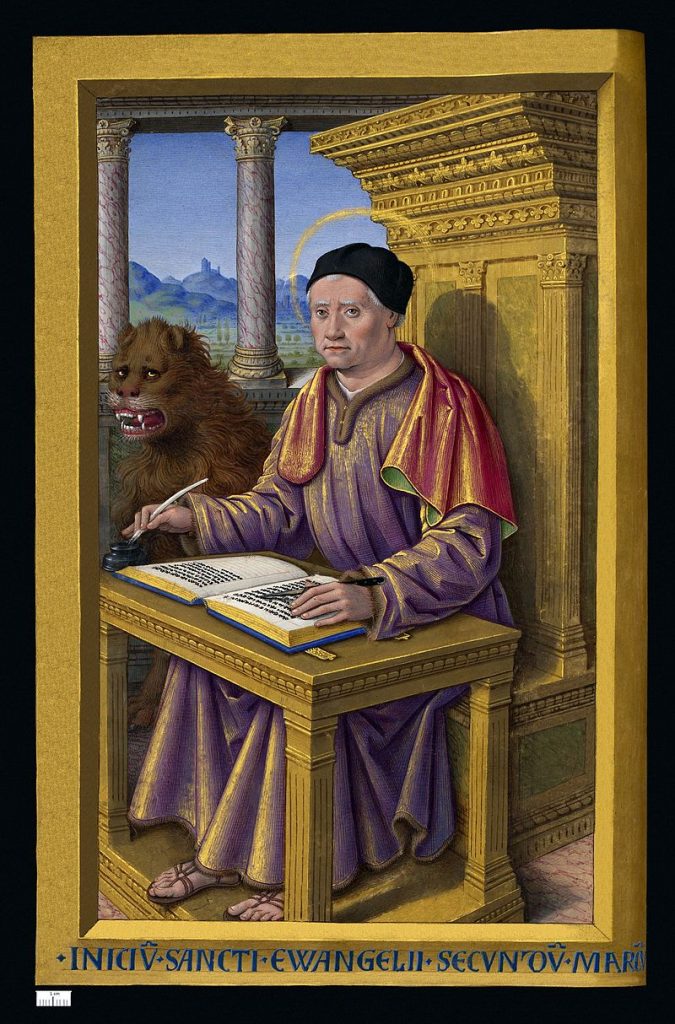

3. If he’s holding a book, there’s a good chance he’s either St. Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, each an author of a respective Gospel.

Recognized as the authors of their eponymous books of the Bible, all of these four are traditionally depicted as holding or writing a book. Thus, they often show up in devotionals or books of hours. The terms “the Evangelist” often follow their names to differentiate between other saints of the same name, if applicable. But how to tell them apart?

- Matthew is often also pictured with an angel, or winged man.

Stephan Lochner’s Three Saints (c. 1450) depicts St. Matthew on the far left and St. John The Evangelist on the far right, with St. Catherine of Alexandria in between. Image c/o The National Gallery & Creative Commons.

Stephan Lochner’s Three Saints (c. 1450) depicts St. Matthew on the far left and St. John The Evangelist on the far right, with St. Catherine of Alexandria in between. Image c/o The National Gallery & Creative Commons. - Mark is often also pictured with a lion.

- Luke is often also pictured with an ox; also sometimes holding an image of the Virgin Mary, physician’s supplies (as he was a physician), and/or painting supplies, (as some traditions hold it that he was also a painter).

- John is often also pictured with an eagle, and sometimes with a chalice with a snake in it, as legend has it he was challenged to drink from a poisoned cup. (Also, an important note: there’s more than one St. John in Christian tradition: this one is St. John the Evangelist/Apostle, not John the Baptist, St. John of the Cross, etc.)

4. If he’s holding a sword and/or a book, it’s most likely St. Paul.

Paul of Tarsus is often depicted with a book, as his letters form a good portion of the New Testament of the Bible, and/or a sword, as that was the means by which he was martyred. (Seeing a pattern with the death instrument attributes? Though modern viewers might see it as slightly morbid, including the instruments that brought about a saint’s death was generally a safe method for identifying Christian saints in western art.)

As we’ve only just dipped our toes into some of the popularly depicted saints in western Christian art, we’ve split this post into two parts in order not to overwhelm you. But overall, we hope this guide helps you discover just what you’re looking at the next time you run into a piece of western Christian art in a museum. Stay tuned for Part II!

*= This artist is featured in our curriculum.

What do we do here at the Art Docent Program? Discover more about us and our curriculum here!

Want more fun art articles? Check out our blog archives for more!

Don’t forget to follow us on Facebook for updates and more posts!