By now, you’re probably an expert at identifying the Christian figures featured in Part I of this guide (and if you haven’t read through it, you can do so here!). In Part II, we’ll be helping you identify even more Christian saints in western religious art, specifically looking at saints who lived after the time of Christ and were popular subjects of Christian art in the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Baroque periods.

So, just how did these saints get the visual codes that help us recognize them, if they aren’t in the Bible? As we mentioned in Part I, in 1260 Jacobus de Voragine published a book called The Golden Legend, which was a collection of stories of the lives of the saints, many of which date from after the time of Christ. It’s not exactly historically accurate, but due to The Golden Legend’s widespread popularity, it impacted visual depictions of saints in religious art for years afterward.

With that being said, let’s dive right back into the fascinating world of religious art, so that you know just what you’re looking at the next time you visit a museum!

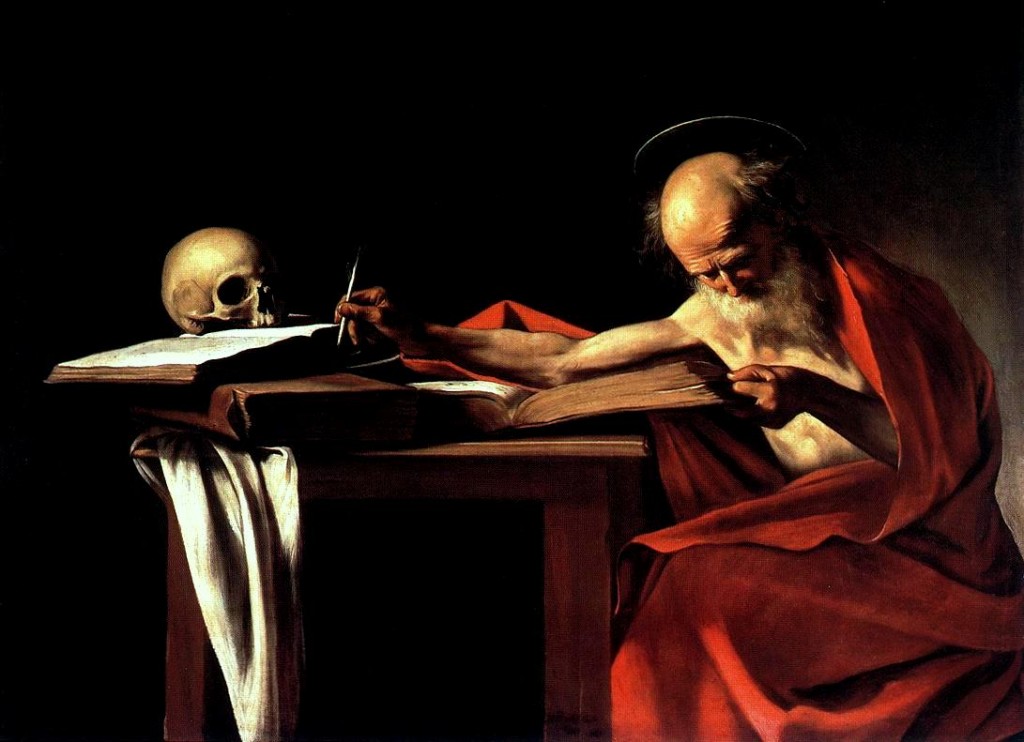

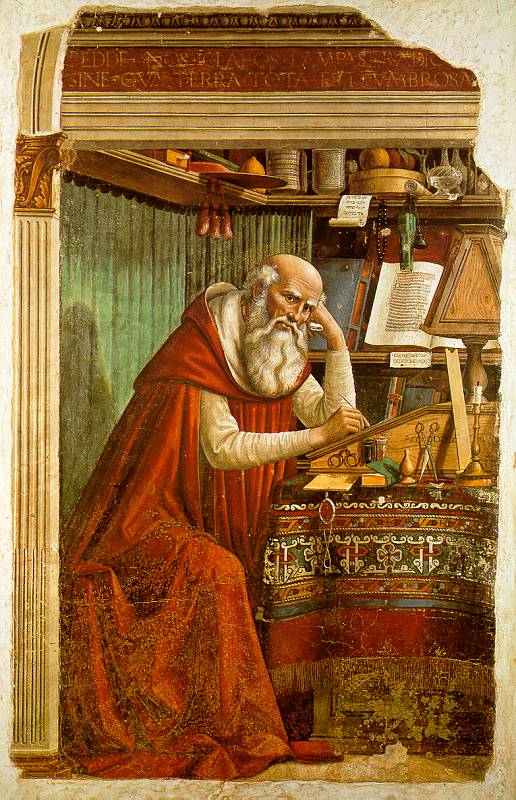

1. If he’s alone, bald, and/or is writing or holding a book, it’s most likely St. Jerome.

Jerome is often pictured alone and with books or writing materials, as he’s known for his Latin translation of the Bible. He may also be accompanied by a lion, since according to legend he tamed a lion by removing a thorn from its paw, and will typically be quite thin, as he is traditionally described as a hermit.

2. If he’s shot full of arrows, it’s most likely St. Sebastian.

According to The Golden Legend, St. Sebastian was martyred during the reign of Diocletian. He was first shot full of arrows, and then, upon his miraculous survival, was killed. Thus, he’s generally pictured with arrows protruding from his body, or holding one, as in the case with the Raphael painting above. He is sometimes pictured with St. Irene.

3. If she’s tending to a man shot full of arrows, it’s most likely St. Irene.

According to legend, St. Irene and her maid rescued St. Sebastian after his attempted martyrdom. If you see a woman in a St. Sebastian painting, it’s most likely her.

4. If he’s fighting a monster or dragon, it’s most likely St. George.

St. George is pretty common throughout western European art, though he’s traditionally from what’s now Turkey. He’s claimed as a patron saint by several countries and regions (including England and Georgia), and churches bearing his name can be found from London to Prague. There are multiple stories associated with the saint, but by far the most famous St. George story is that of the St. George and the dragon, which probably serves as a basis for a lot of early modern fairy tales. According to The Golden Legend, in St. George’s travels, he came across a village plagued by a dragon. The townspeople would appease the dragon by drawing lots for who would offer the beast both sheep and a human for it to gorge on. As George was passing through, the lot fell on the king’s daughter, and she was offered up to the dragon. St. George, being a righteous man, was able to help her control the dragon and eventually killed it, and the town subsequently converted to Christianity. This story is the one that’s most commonly depicted in art, and what a variety of artwork there is! We’ve chosen two examples by Italian artists Paolo Uccello and Tintoretto for this post, but, there are loads more worth exploring, as there are for the rest of the saints on this list as well.

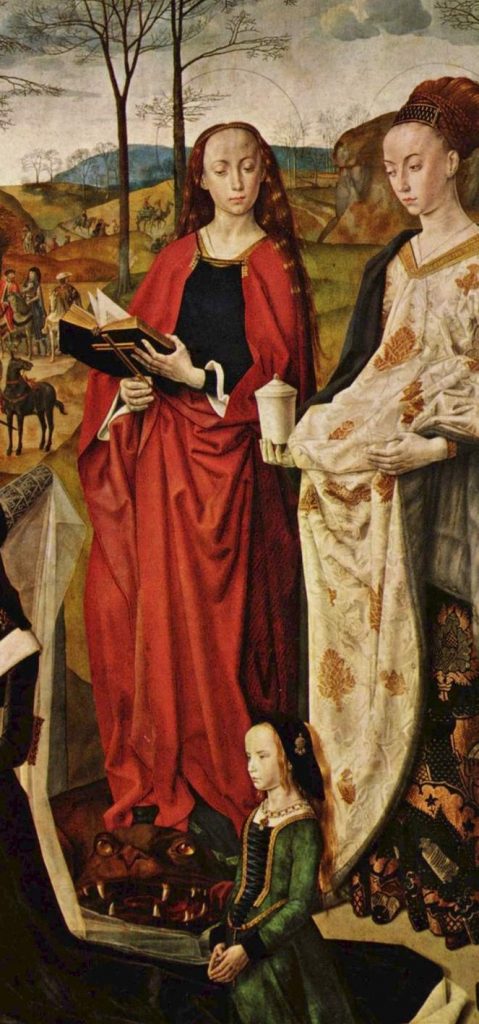

5. If she’s near a monster alone, it’s most likely St. Margaret of Antioch.

According to The Golden Legend, St. Margaret of Antioch was a virtuous Christian woman who was imprisoned when she refused to marry a non-Christian prefect. At some point, a dragon or monster associated with the devil appeared and attacked her, at which she (according to various traditions) either made the sign of the cross at which the monster disappeared, or was swallowed whole only to have the creature split asunder when she made the sign of the cross from its stomach. While it makes for really visually intriguing art, as St. Margaret is almost always pictured with a monster of some sort, even The Golden Legend notes that the tradition of the beast swallowing her is “apocryphal,” and meant to be understood as such.

7. If she’s holding a wheel, it’s most likely St. Catherine of Alexandria.

St. Catherine of Alexandria is also a fairly common saint in western Christian art. Like many other saints, she’s most commonly recognized by her instrument of torture; a wheel. According to legend, after many rounds of other forms of torture, St. Catherine was sent to be tortured on a wheel. It miraculously broke, and she was subsequently martyred by beheading. You’ll often see St. Catherine depicted with her wheel, or with it just in sight nearby.

Though this list is by no means a complete record of Christian saints and attributes in western art (as there are quite a few that people in more art historical periods would be more familiar with than us), we hope it helps you the next time you visit a museum with lots of Christian western art.

Interested in further reading? Check out Part I of our guide, as well as this very basic rundown on Wikipedia, and learn more about The Golden Legend here!

What do we do here at the Art Docent Program? Check out more about us and our curriculum here!

Want more art historical reads? Read more on our blog archives, and don’t forget to follow us on Facebook!

*= This artist is featured in our curriculum.